Farewell! Six Memorable NYC Hotels Closed Permanently By The Pandemic

The last 18 months have been a rough ride for New York City hotels. More than 30 percent of the city’s 705 properties shut down during the pandemic. And while dozens have reopened, it’s still anybody’s guess how many will ultimately return. What we do know is that at least 30 won’t be coming back, according to the Hotel Association of New York.

The hotels that checked out are a mixed bag of properties large and small, independents and chains, places you’ve never heard of and hotels so famous, so entrenched in New York City culture, that they seemed almost immortal. Not every shuttered hotel was a gem. But each provided employment for dozens of workers, paid taxes that supported the city, enlivened the neighborhood and extended hospitality, whether exemplary or less so, to some of the 66 million visitors who descend upon New York in a good year. And that doesn’t include the many locals checking in during a renovation, an altercation, a staycation or just after a long night.

With that, we offer our first batch of NYC hotel obituaries — six Covid casualties we couldn’t let disappear without a few words of appreciation. It won’t be our last.

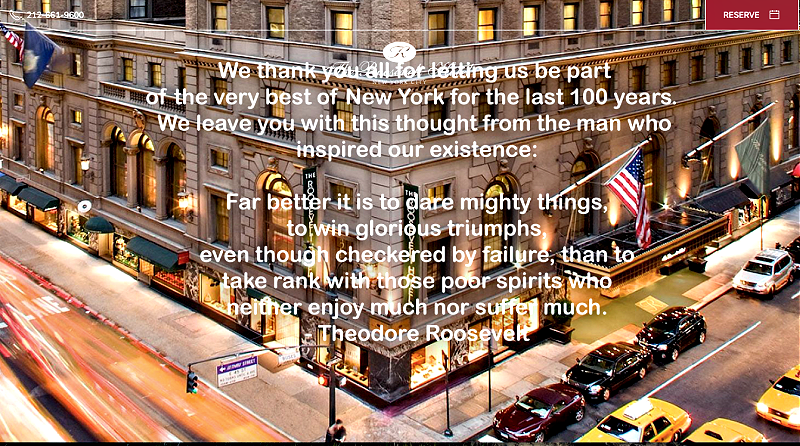

The Roosevelt Hotel website says farewell (Roosevelt Hotel photo)

The Roosevelt Hotel

As pandemic exits go, it’s hard to top The Roosevelt Hotel. Look no further than the gracious farewell message still posted on their website (above) almost a year after the hotel’s demise. The Roosevelt (named for Teddy) was a class act for much of its long life, a big deal in a big building that ate up an entire city block. The Brobdingnagian brick building, the brainchild of architects George B. Post & Sons, was groundbreaking in 1924 as one of the city’s first to employ a “set back” architectural style. A radio in every guest room was another Roosevelt first. In 1948, presidential candidate Thomas Dewey mistakenly announced he had defeated Harry Truman from his headquarters at the Roosevelt. And with an eye-catching Grand Hotel lobby adorned with extravagant, Roaring 20s accoutrements like gilded Corinthian columns and stupendous crystal chandeliers, the Roosevelt was for decades an answered prayer for locals and travelers alike — an iconic, history-drenched, sofa-rich space to meet (the Big Clock was a landmark), rest your feet, have a drink or just imagine yourself in a classic New York City movie (Wall Street, Malcolm X, Men in Black 3 and The Irishman, among others, were filmed here).

Like Grand Central Station, to which the hotel was umbilically linked by an underground passage, the Roosevelt had a knack for inserting itself into popular culture, from mid-century bandleader Guy Lombardo’s celebrated New Year’s Eve broadcasts from the Grand Ballroom to episodes of The Bachelor taped there. The years took a toll as evidenced by the 1,015 guest rooms, hopelessly dated despite fresh carpeting, energetic Roosevelt Red walls and other Hail Mary decorating efforts. In recent years, tourists, conventioneers and flight crews were their primary occupants (Pakistan International Airlines owns the hotel). The pandemic, coupled with mounting debt and the prospect of exorbitant infrastructure repairs, proved fatal. So we’ll send off this enduring landmark with a favorite memory of the lobby’s spirit-lifting holiday tree, a-glitter with glass balls and crowned with the ultimate topper: a Roosevelt crystal chandelier.

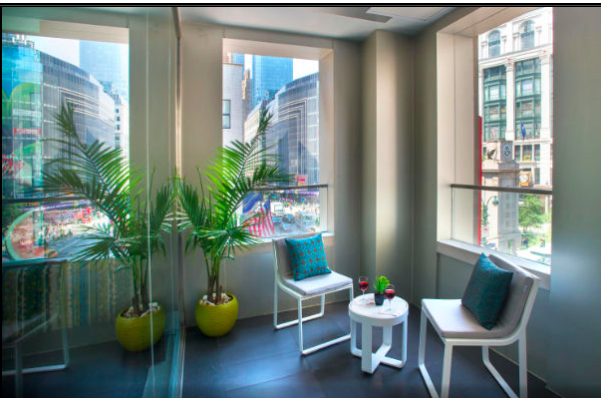

Small but perfectly former: a Hudson guest room (Hudson photo)

Hudson

Nothing stays hip forever, which may explain why Hudson didn’t make it through the pandemic. With multiple bars, a pool table in the library and a rakish attitude, this exuberant, 878-room Philippe Starck/Ian Schrager collaboration from 2000 transformed a decrepit SRO hotel in a massive 1928 brick building into a mind-bending play space for guests on a budget. Rooms were minuscule but beguiling, pieced together like sleek burr puzzles with style to spare — African makore wood walls and floors, snowy bed linens and in each a mirror-shiny, stainless steel Hudson chair (Emeco still sells them; we have one in our kitchen). The cavernous, flamboyantly styled public spaces — skylit library, cafeteria-style restaurant, indoor and outdoor bars — almost compensated for the tight quarters. We loved the surprises Hudson cooked up early on, like the Semi-Automatic, a cheeky vending machine stocked with gold-plated handcuffs, sequined miniskirts and Ouiji boards instead of Doritos and M&Ms. We didn’t love ridiculous high season prices that could hit $500 a night. Still, for a trendy boutique hotel, a 20-year run is an eternity.

Update: In November, the shuttered Hudson was sold by SBE Entertainment to Eldridge, a holding company whose Cain International real estate portfolio includes the Waldorf Astoria Beverly Hills and the Beverly Hills Hotel. Expect whatever becomes of 356 West 58th Street to look very different from Hudson.

New York Marriott East Side, the former Shelton Hotel, shows off its height (Overnight New York photo)

New York Marriott East Side

Gaze up at the the New York Marriott East Side’s massive Roman Revival building, and you’ll see everything that made this towering hotel remarkable. Start with the arched limestone base that’s weirdly reminiscent of a de Chirico painting, move up to the three brick “set backs” that revolutionized 1920s architecture, and stop at the all-important 31st floor, proof positive that this was the world’s tallest skyscraper when it opened in 1923. As the tony Shelton Hotel, the property started life as a 1,200 residential hotel for men, outfitted smartly with a bowling alley, swimming pool, billiard tables and squash courts. It flopped and within a year morphed into a co-ed residential hotel that counted among its guests photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his wife, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, who painted East River from the Shelton Hotel in 1927 from their 30th-floor window. (You can see it at The Met.) Another Shelton brush with fame came in 1926, when escape artist Harry Houdini spent an hour and a half submerged in the hotel pool in an airtight, coffin-like box equipped with an emergency telephone. “Anyone can do it,” he told The New York Times.

Alas, the Shelton didn’t age well. With just 11 residents and decaying quarters, talk of teardown began in 1974. It ended in 1990 when Marriott took over, flush with a $25 million infusion from Morgan Stanley, the building’s owner. They gutted the place, renovating the rooms and upgrading public spaces. That was 30 years ago. The Marriott East Side looked outdated and empty when we stopped by shortly before the pandemic. Not a good candidate for surviving Covid-19, in other words. But the historic exterior still stands tall at 525 Lexington Avenue.

A sitting room with a parade view at the Courtyard Marriott Herald Square (Courtyard Marriott Herald Square photo)

Courtyard Marriott Herald Square

New York has no shortage of Courtyard Marriotts, but the Courtyard Marriott Herald Square was unique. The hotel was the only Courtyard — or hotel for that matter — situated steps away from Macy’s and the grand finale of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Originally home to the Atlantic Bank of New York, the 1928 limestone building was destined for parade watching with more than 14 floors of guest-room windows facing the festivities and an open-air terrace connected to the upstairs lobby for alfresco balloon viewing. The location was also super sweet for parade enthusiasts who doubled as Black Friday door busters. With high hopes and great fanfare, the 167-room Courtyard Herald Square opened in 2013. Mayor Michael Bloomberg cut the ribbon. Whether New York needed another hotel in Herald Square — the Courtyard was the third to open that year — was anyone’s guess. But no one has ever disputed the need for more hotels with windows overlooking the big parade. And now, there’s one less.

A room with a parade view at The Excelsior (Excelsior photo)

The Excelsior Hotel

Homey, functional and utterly unexceptional, The Excelsior Hotel had one big asset: a million dollar location steps from Central Park and the American Museum of Natural History. Families checked in to see the museum’s dinosaurs, meteorites and gigantic blue whale. And they descended en masse at Thanksgiving to gaze from their windows as the balloons for Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade were inflated on the street below. The family-size rooms dated from the 200-room Excelsior’s origins as a residential hotel in 1922 called Hotel Standish Hall, named inexplicably for the Pilgrim’s brutal advisor, Myles Standish. Sometime in the 1950s the name changed, and the Excelsior thrived as a congenial budget property with paint-caked walls, cheerfully mis-matched furniture and a vintage coffee shop overseen by a hostess who sashayed about in an evening gown and marabou feathers as she seated bemused tourists and locals for bagels and eggs. She was gone by 1997, when a renovation bumped the hotel upmarket a notch. A subsequent redo in 2010 upgraded everything including the wood paneled, pink-marble lobby, and almost yanked the Excelsior into the 21st century. But it wasn’t enough, and the hotel checked out during the pandemic, two years shy of 100 years in business.

Update: In late December 2021, the Excelsior sold for close to $80 million to a developer that specializes in turning buildings into high-end residential rentals. In other words, New York’s lone hotel overlooking the American Museum of Natural History — and the balloon-inflation for Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade — isn’t coming back.

The Omni Berkshire lobby at the time of the hotel’s closing (Omni Berkshire Place photo)

Omni Berkshire Place

We didn’t see this one coming. The 395-room Omni Berkshire Place was a comfortable, well reviewed business hotel with a glamorous history and a family- friendly streak. (Sarah Palin checked in, kids in tow, when she appeared on Saturday Night Live in 2008.) Opened in 1926, the Berkshire Hotel was part of Terminal City, a constellation of Classical Revival hotels and residential buildings orbiting Grand Central Terminal. A stellar location, unusually large rooms and five-star hotel services attracted socialites, upscale artists and theater royalty like Ethel Merman, who lived there with her mother, and Richard Rodgers, who hatched the musical Oklahoma! with Oscar Hammerstein over lunch in the hotel’s exclusive Barberry Room (regulars included Alfred Hitchcock, Edward R. Murrow and Salvador Dali). Those heady days had ended by 1977, when Ireland’s Dunfrey Family Hotel Company snapped up the property, renaming it the Berkshire Place and adding Omni to the name after acquiring Omni hotels. But the hotel remained a class act. It changed hands for the final time in 1996 when Texas-based TRT Holdings purchased Omni and fashioned the Omni Berkshire Place as a welcoming blast of Texas on the East River. In a salute to TRT co-founder Robert Rowling, the hotel’s manly, wood-paneled steak and chop house was named Bob’s.

Update: Surprise! Despite the Omni’s well-publicized, lock-stock-and-barrel closing in 2020, turns out it wasn’t permanent. The hotel reopened in on November 1, 2021 — and celebrated with a sprightly decorated holiday tree in the lobby and staff members thrilled to be called back to work, as an Omni porter told us. Turns out it was less costly for the hotel to reopen than for owners to pay city-mandated severance to out-of-work staffers. “Our strategy was to lose less, so what do we do?” Peter Strebel, president of Dallas-based Omni Hotels & Resorts, told Crains. “Paying the severance would have cost more than reopening.” Welcome back!

A second batch of hotel obits will be coming soon.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!