The Surprising Way Hotels Facilitated The Art of Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper’s lifelong obsession with New York City is well known as is his fascination with urban landscapes, peering into private rooms and the loneliness and isolation a teeming metropolis can breed.

Hotels embody all of the above, so it’s surprising in a way that he didn’t draw inspiration from them as he did from apartment buildings, restaurants and theaters.

But hotels facilitated a small but intriguing slice of the celebrated 20th-century artist’s work, as the Edward Hopper’s New York, on view at the Whitney Museum through March 5, shows. They helped him pay his bills and captured his interest early in his career, if only for mercenary reasons. And that’s more than enough to make this satisfying exhibition catnip for art-loving hotel geeks.

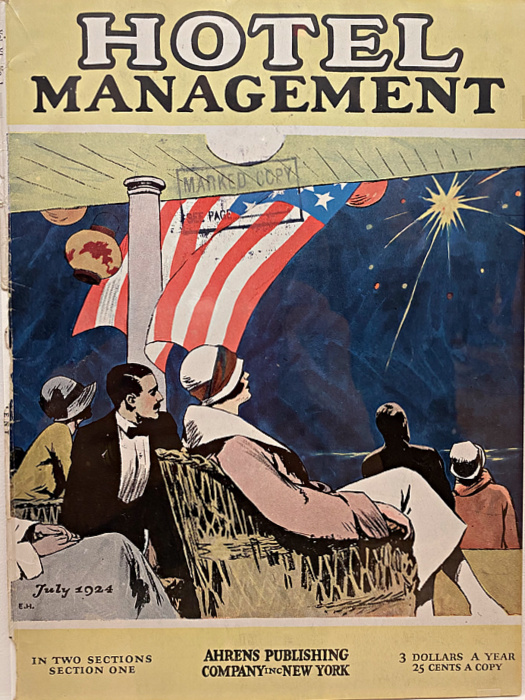

Hotel Management magazine, July 1924, cover art by Edward Hopper

Like many of his early 20th-century contemporaries, including the artists Arthur Dove, John Sloan and Reginald Marsh, Hopper began his career in commercial art as an ad designer and illustrator. Though fine art was his end goal from a young age, he initially studied commercial art, pressured by his parents who worried about his ability to make a living as a painter.

They weren’t wrong. Hopper had no success as a fine artist early in his career. But he flourished as a commercial artist, producing hundreds of drawings and occasional oil sketches for trade and in-house magazines and advertisements between 1906 and 1925.

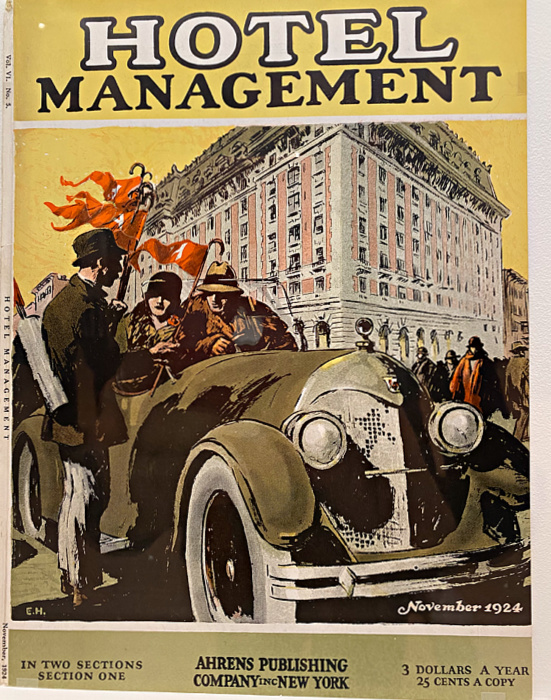

Hotel Management, November 1924. Note the initials in the lower left corner.

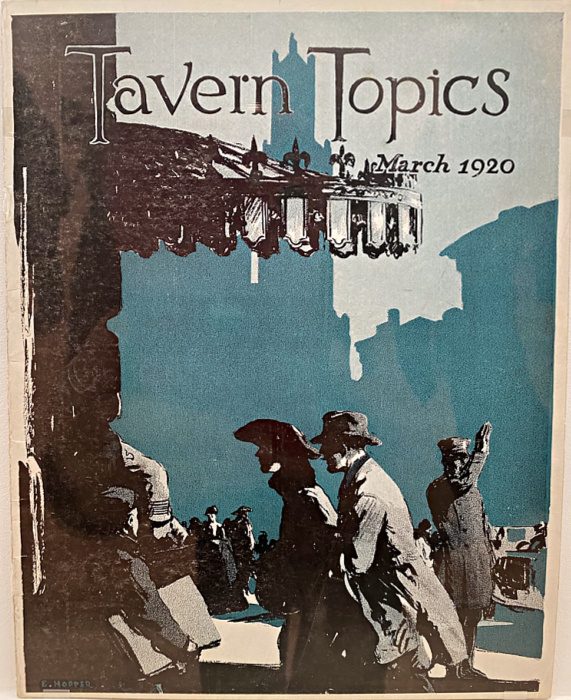

And that brings us to hotels. Hospitality publications were a mainstay of Hopper’s adventures in the early 20th-century’s version of gig economy, notably Hotel Management, a monthly periodical aimed at the industry’s executive and administrative staffers, and Tavern Topics, created for guests at the glamorous Waldorf Astoria.

They offered a dashing addition to a freelance CV packed with assignments from publications like The Bulletin of the New York Edison Company and Morse Dry Dock Dial, produced by a Brooklyn shipbuilder to boost employee moral and tamp down labor union efforts.

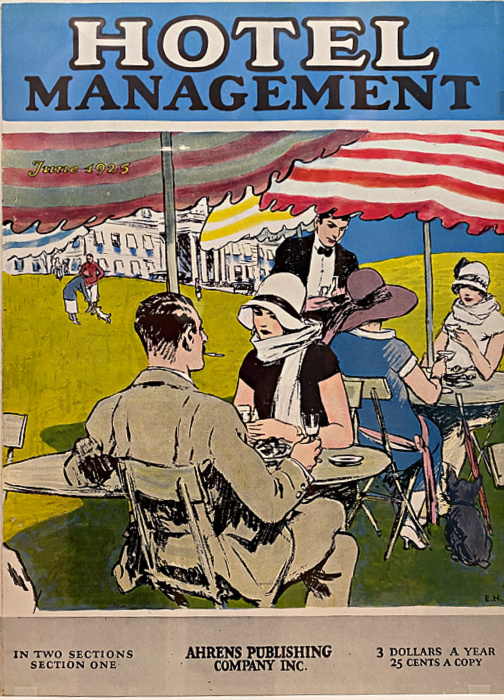

Hotel Management magazine, June 1924

Hopper loathed the creative restrictions that commercial artwork imposed and dismissed his illustrations and ad designs as “potboilers.” “Sometimes I’d walk around the block a couple of times before I’d go in, wanting the job for the money and at the same time hoping to hell I would not get the lousy thing,” he told an interviewer later in his career.

Yet, his successful commercial art forays proved a significant stepping stone, both creatively and professionally. Years of experimenting with color pairings and bold graphics for his magazine covers provided insights he’d transfer to his paintings. And by the late 1920s, Hopper’s acclaim as an illustrator landed him in the art department at Scribner’s, where he was able to gain a taste of artistic freedom, picking and choosing his assignments. By then, his career as a painter was taking off. The rest, as the magnificently moody, color-drenched walls of the Whitney attest, is art history.

The Waldorf Astoria’s Tavern Topics, March 1920, cover art by Edward Hopper

Despite his disdain for commercial art, Hopper squirreled away a substantial cache of his printed illustrations, including proofs, magazine covers, covers designs and tear sheets, much of it donated to the Whitney by Josephine Hopper, his wife of 43 years. He must have known its value, if only subliminally. His designs for Hotel Management and Tavern Topics, among others, are skillful and charming — and offer hints of what was to come.

Hopper did use hotels to explore his recurring themes of loneliness and alienation in several paintings, notably Hotel Lobby (1943), an oddly unsettling depiction of an older couple and a young woman near a deserted hotel check-in desk (Indianapolis Museum of Art Collection), and Hotel Window (1955), reminiscent of a moody Jean Rhys novel with of a woman, swathed in a fur-collared coat and a red hat and seated by a window (private collection). A shame they didn’t make it into the show for the hotel nerds in the audience.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!