The New York Hotel You’ve Never Heard Of That Inspired Georgia O’Keeffe’s Skyscraper Paintings

On a recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I chanced upon Georgia O’Keeffe’s panoramic painting from 1928 of the East River. A muted geometry of belching factory smokestacks and brackish water, it’s the elegant, if downbeat, work of an artist becoming visibly disillusioned with urban life, a good-bye-to-all-that rendering of the city she’d soon abandon.

But what really caught my attention was the title “East River from the Shelton Hotel.”

“East River from the Shelton Hotel” (1927) by Georgia O’Keeffe — Metropolitan Museum of Art photo

From 1925 to 1929, O’Keeffe lived on the 30th floor of Manhattan’s Shelton Hotel with her husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. With the possible exception of the Hotel Chelsea, it’s hard to think of another New York City hotel that’s had such a profound effect on an artist, especially a hotel you’ve probably never heard of.

Towering over Lexington Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets, the 31-story, 1,200-room Shelton Hotel was hailed as the tallest skyscraper in the world when it opened in 1923. Not only was it tall, it was a rarity — an elegant residential hotel for men with a bowling alley, billiard tables, squash courts, a barber shop and a swimming pool. It soon became clear why there weren’t more hotels like it. By 1924, the all-male Shelton was bleeding money and morphed into a classic co-ed residential hotel, catnip for renters like O’Keeffe and Stieglitz.

Postcard rendering of the Shelton Hotel

What was never in doubt was the building’s architectural significance. With a tasteful two-story limestone base and three brick setbacks stepping up to a central tower, the Shelton was groundbreaking. Critics deemed it the first building to successfully embody 1916 zoning requirements that prescribed setbacks to keep skyscrapers from becoming hulking eyesores. The Empire State Building is just one of the buildings the Shelton influenced. As late as 1977, New York Times art critic Ada Louse Huxtable declared the hotel a “landmark New York skyscraper.”

O’Keeffe couldn’t have asked for a more agreeably situated studio. From her airy lair, she enjoyed unimpeded, bird’s eye views of the river and the city’s growing crop of skyscrapers. Like Charles Demuth, Charles Sheeler and other artists of her era, O’Keeffe was fascinated by skyscrapers as a symbol of urban modernity, a core principle of Precisionism, the Post-World War I modern art style that celebrated America’s dynamic new landscape of bridges, factories and skyscrapers.

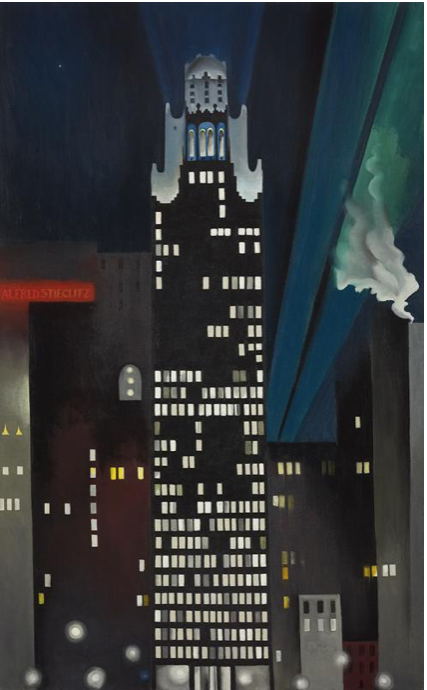

Ensconced in her Shelton perch, O’Keeffe created at least 25 paintings and drawings of skyscrapers and cityscapes. Among her best known is “Radiator Building — Night, New York,” a masterful celebration of the skyscraper mystique — and the iconic black and gold American Radiator Building — that all but whistles a Gershwin tune. (The building is now the glamorous Bryant Park Hotel.)

The Radiator Building — Night, New York” (1927) by Georgia O’Keeffe — Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art photo

The Shelton itself landed a starring role in “The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y.,” an abstract feast of circles and rectangles that softens the hard edges of the massive skyscraper. As O’Keeffe recalled, “”I went out one morning to look at [the Shelton Hotel] and there was the optical illusion of a bite out of one side of the tower made by the sun, with sunspots against the building and against the sky.”

“The Hotel Shelton with Sunspots” (1926) by Georgia O’Keeffe — Art Institute of Chicago photo

Serving as an urban muse for O’Keeffe wasn’t the Shelton’s only brush with notability. It was built by James T. Lee, the architecturally savvy developer of luxurious apartment buildings and the grandfather of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, née Jacqueline Lee Bouvier. Arthur Loomis Harmon, the architect of the Shelton, went on to help design the Empire State Building. (He also created Allerton House, a towering 1916 residential hotel that’s now the budget-friendly Pod 39 hotel.)

But the Shelton’s renown shot sky high after a visit to the basement swimming pool in 1926 by the escape artist Harry Houdini. Sealed in an airtight, coffin-like box (albeit one equipped with a telephone in case of an emergency), Houdini was lowered into the pool where he lay submerged for an hour and half. He emerged on schedule, fatigued but alive. “Anyone can do it,” he told The New York Times.

New York Marriott East Side, formerly the Shelton Hotel

Alas, the Shelton did not age gracefully. By 1974, the hotel housed just 11 permanent residents and decay had set in. There was talk of razing the building to make way for a block-long office tower. All that ended in 1990, when Marriott took and, fueled by a $25 million infusion from Morgan Stanley, the building’s owner, gutted the place, renovating the rooms and upgrading the public spaces.

And the Shelton today? It’s the New York Marriott East Side, a 646-room hotel with a sprawling lobby and multiple meeting rooms, including one named for Georgia O’Keeffe. Unfortunately, the hotel is little changed since its 1990s renovation and all but crying out for a reboot, a situation reflected in the bargain prices that are often offered.

O’Keeffe, however, would instantly recognize the towering Romanesque Revival exterior that inspired her. It’s still quite a looker.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!