Checking into “Hotel Life,” A New Book About The Places Where Anything Can Happen

Hotels are embedded in our lives, and not just when we travel. They’re welcoming places, standing at the ready with a bar where you can meet friends, a lobby offering shelter on an inclement day and a restaurant that’s often one the best in town.

Hotels are embedded in our lives, and not just when we travel. They’re welcoming places, standing at the ready with a bar where you can meet friends, a lobby offering shelter on an inclement day and a restaurant that’s often one the best in town.

We attend weddings and conferences at hotels. Some of us have memberships in hotel gyms. As unofficial local landmarks, the best hotels exude a promise of glamour, adventure and serendipitous surprise. Walking home from my first job in New York, I often strolled through The Plaza. One day I whirled through the revolving doors with Mick Jagger.

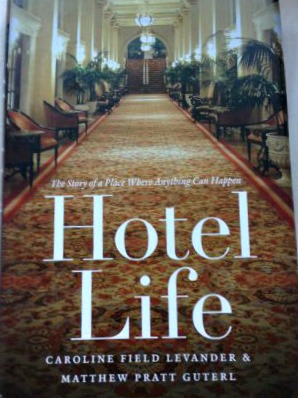

But this is just the warm-up to the much larger role hotels play in modern life, as authors Caroline Field Levander and Matthew Pratt Guterl put forth in their new book Hotel Life. Tantalizingly subtitled The Story of a Place Where Anything Can Happen, the book presents hotels as powerful social institutions, not unlike universities, hospitals and even prisons, that embrace all walks of life and offer insights into who and what we are. Or as the authors put it, “hotels cut to the core of what it means to be human in modern times.”

That’s a tall order for a Holiday Inn. But that’s their point — viewed collectively, hotels are much more than a bed for the night with a mint by the pillow. As democratic institutions open to anyone with the money to check in, hotels have held a mirror to society for nearly 200 years, reflecting changing views on lifestyles, wellness, sexuality, food, fashion, economics, politics, religion and design. Hotels have been on the front lines in dealing with issues of class, sex, gender and race. As depicted in classic movies like 1932’s Grand Hotel, hotels are microcosms, where a savvy social historian can drop a bell jar over a swath of humanity and explore anything from cultural imperialism to methods of suicide.

It’s this big picture, not thread counts, that fascinates the authors. In this slender volume they go broad, mining film, literature, magazine articles, advertisements and the internet to explore the hotel as an all-encompassing life force. Sidestepping chronology, they organize their material around contrasting themes — space (public vs. private), scale (rich vs. poor), affect (fortune vs. failure) — that unite, on some level at least, the wildly diverse family of hotels, from luxury, resort, business and boutique to flophouse.

The hotel as we know it is an American invention, a potent if unlikely blend of democracy and hospitality fueled by a young nation’s new-found mobility. Deeming taverns and primitive B & Bs unsuitable for incoming visitors, a nameless government official ordered up plans for the nation’s first hotel, to be built by the Potomac. By the 1820s, hotels had become must-have emblems of a city’s economic vitality, brandished by early adopters like Boston, Baltimore and Philadelphia.

History duly noted, the authors pepper their narrative with enticing details, like President Ulysses S. Grant’s coinage of the word lobbyists — “damned lobbyists” to be precise — to describe the swirl of favor seekers who besieged him when he sought solace in brandy and cigars in the neoclassical foyer of the Willard Hotel in the 1870s.

Bibles, we learn, were placed in hotel rooms by evangelicals to counteract what they saw: an invitation to illicit sex in the form of a freshly made bed, closed doors and ambient anonymity. (Among those unaffected by the Good Book’s presence was actor Charlie Sheen, whose ripped-from-the-headlines exploits at The Plaza are described in minute detail to illustrate everything Bible enthusiasts sought to prevent.)

In a timely aside, presidential candidate Donald Trump emerges as the grinch who booted Kay Thompson, author of the iconic Eloise books, from her rent-free room at The Plaza after his purchase of the hotel in the 1980s. Thompson retaliated by denying Trump the right to use the sassy six-year-old to promote the hotel, a move overturned only after her death. (Given the gold mine Eloise has proved to be for the hotel since 2009, Trump showed extremely poor judgment.)

Much that the authors include isn’t new to anyone with a passing interest in hotels or American culture, but when presented to illuminate their points the familiar becomes fresh. Given the sheer juiciness of their best stuff, I wish they had reigned in their natural instincts and written the book for a more general audience. Both authors are academics. The result is sentences like this:

“For anyone interested in the globalized world of the present, the stakes of Hotel Life should be abundantly clear: as worldwide movements and circulations increasingly become common, and as notions of the self shift to an internationalist mode, the institutional armature enabling and frustrating fully realized iterations of this self change, too.”

Plow past that, and you may well be glad you checked into this clever take on hotel life.

Hotel Life: The Story of a Place Where Anything Can Happen, University of North Carolina Press; 224 pages; $29.95

What a fantastic write-up and review. Worthy of the NYT Book Review (they should be so lucky…). And I can’t imagine the authors will have a more gracious promoter. The only thing better: if the book had been written by you.

Thanks for reading (and the kind words). Much appreciated!

Thanks for distilling the essence of the book. A fascinating subject indeed.

With thanks, John.